Ten Top Tips for Interviewing Relatives

[This article first appeared in the now obsolete Discover My Past Scotland 2008]

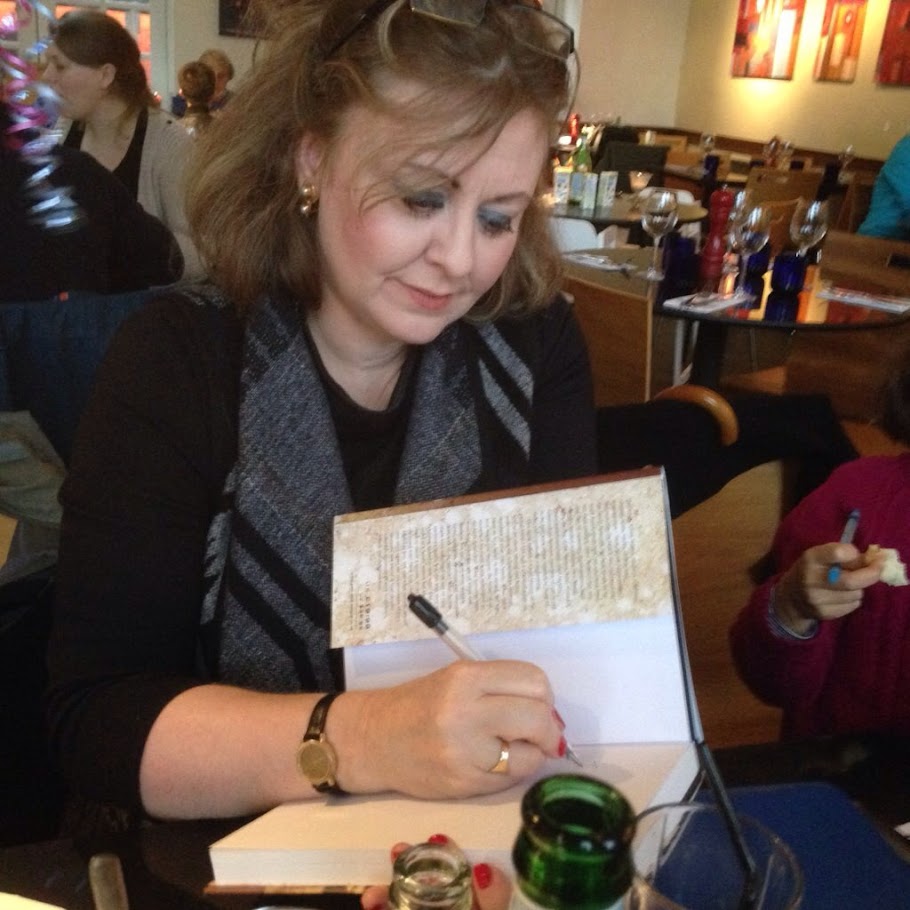

Chatting to as many relatives as possible – and as many

times as possible - when you are doing family history research really can pay

off. Remember that in an oral interview, only 10% of the talking time should be

taken up by you, the interviewer; the other 90% should be time for the interviewee

to talk.

|

At ease. Make sure your interviewee is as relaxed as

possible and use prompts to jog his or her memory.

|

There is always the chance that an odd detail will emerge

from an oral interview that could lead you into new realms of investigation in

the archives, or by way of censuses and certificates. But remember also, that

family history is not simply about coming up with a list of dates and facts to

add to your family tree diagram. It is also about getting a feel for the way in

which your family lived in the past, and finding out about the kind of people

they were. Once you know your characters, their setting, their education and

places of work you will more easily be able to understand why they made the

life decisions they did.

To put your interviewee at ease and to maximise the likelihood

of new information emerging, try the ten strategies below:

1. Prepare

your questions in advance. Don’t read a list of questions from a card or

paper as this can be offputting to the interviewee, but do have some idea

of what you want to find out.

2. Use prompts

– items that you can hold and examine such as commemorative tankards and

photographs can provide great talking points.

-

Always

ask single questions. Don’t confuse the interviewee by asking two

questions at once.

- Don’t

ask leading questions (i..e. questions that make assumptions). Don’t say

‘He must have felt terribly poor growing up in such a small house,’ Say

‘How do you think he felt growing up in that house?’

- Ask open

rather than closed questions. A closed question might be ‘Was Uncle

Charlie happy about the birth of so many children?’ This might elicit a

‘Yes’ or ‘No’ type answer. Ask instead, ‘How do you think Uncle Charlie

felt about the birth of so many children?’ Such open questions allow

people to talk freely and this is when unexpected information may slip

out. Also, put the questions in different ways on different occasions. For

example, to ascertain when certain events happened, rather than asking for

specific information with a question such as ‘Which year was that?’ ask

for the same information in a roundabout way with a question such as ‘Was

Aunty Grace born at that time?’

- But

don’t make your questions too open. Asking an interviewee what they

remember about work in a particular factory or shipyard, for example,

might throw them into a panic. Ask instead what they remember about their

first day in the job, or how they spent their first pay packet.

- Look

out for the silences. There may be significant reasons why your

interviewees don’t mention particular relatives or particular times.

Illegitimacy, divorce and periods in prison are just some of the secrets

that members of the older generation may be unwilling to discuss. Be

sensitive to these awkward moments and make a mental note to check up on

them later.

- Make

sure you double check when accounts given by relations seem to be

contradicting each other. Incorrect memories can be as interesting as

correct ones. There may be a significant reason for them.

- Always

ask – on the off chance – whether there is anything in print (or written

down) about the story you are discussing. Relatives often have newspaper

clippings, diaries, old school magazines, autograph books (and many other

items that they assume will not be of any interest to anyone) tucked away.

You can nearly always learn something from these.

|

Is it in writing? This diary that my father kept as a boy

during the Second World War substantiates his oral account of the same period.

|

10. Think about how you will

record the answers to your questions. You could get the interviewee to write

their own responses, or tape what they are saying. The best way is probably to

jot down rough notes as they are talking and write these up as soon as possible

after the interview.

Keywords: family history, European ancestors, oral history, interviews, England