If you enjoy this article, why not follow me for more creative approaches to family history?

Twitter: https://twitter.com/RuthaSymes

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Searchmyancestry/

All Girls Together

- taking a look at the relationships between sisters in your family history

For many young women in the past, relationships with sisters

were probably the longest-lasting connections of their lives – vastly

outspanning their relationships with their parents and their own children. If

you discover branches heavy with sisters on your family tree, consider

carefully the age gaps between them, when and whom they married, where they

ended up living, whether or not they had children and the ways in which their

lives may have consequently merged and diverged. The chances are that the

relationships between them – whether they were nurturing or hostile (and they

were probably at different times both) - were one of the central features of

their experience.

|

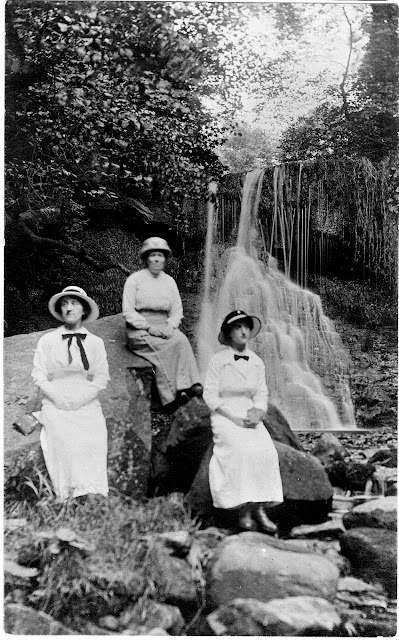

| Adult sisters abroad c 1910. Author's own collection |

Click here for more on books by Ruth A. Symes (UK)

Most of what we know about relationships between sisters in

the past focuses on middle- and upper-class girls. It has been suggested that

close emotional bonds between sisters really developed only in the late

eighteenth century. Before this sibling relationships in general were less

affectionate. This was partly due to the high instance of childhood mortality

(something which meant that families invested less emotionally in each child),

and partly due to the rivalry and conflict that could occur between siblings

over inheritance practices and marriage customs. In the late eighteenth

century, it has been argued, sisters became closer and less competitive than

they had been in earlier ages. Whilst brothers were away from home at private

schools or in military regiments, girls stayed at home until marriage and were,

therefore, thrown upon each other’s company for more lengthy periods.

In the nineteenth-century, bonds of affection between

sisters grew ever deeper. There was a new emphasis on the role of love in

family life and parents emphasised the need for harmony and co-operation

between their children. The existence of large families often meant that

younger girls were partly parented by older sisters. Where girls were educated

at home, the role of the elder girls could be that of teacher to her younger

female siblings. Evidence of sisterly relationships in the Victorian period

comes through personal paperwork such as letters and diaries. From these it is

apparent that, on many occasions, the close bonds of sisterhood helped women to

overcome emotional and financial difficulties and stimulated creativity -

anything from shared needlework projects to clutches of novels all produced

within the same family home.

In the twentieth century, families tended to be smaller with

the result (according to some psychologists), that children competed more for

maternal affection. There was an increase in sibling rivalry and jealousy

particularly amongst young children. As the century progressed, there was a

focus on the individuality rather than the similarity of siblings (separate

beds and bedrooms for each child, for example) and, with the advent of sexual

equality with brothers, sisterhood was no longer quite the intense domestic

experience it had once been.

Sisters and Marriage

You should pay particular attention to the dates of marriage

amongst groups of sisters on your family tree. Whatever their relationship as

children, the testing time for sisters came when they were old enough to be

betrothed. Victorian letters and diaries reveal that sisters often experienced

deep pain when they were separated from each other, even by pleasant events

such as courtship and marriage. From the wedding day onwards, the lives of

sisters (which had previously been almost interchangeable) could become widely

divergent depending on the wealth, background and character of the prospective

husbands.

It was important in families of good social standing for

girls to get married in order of age and to marry men with similar social

aspirations. The five daughters of Mrs Bennet in Jane Austen’s Pride and

Prejudice (pub. 1813) are a

constant worry to their mother since all of them are ‘out’ (i.e. old enough to

appear in public at balls and dances) and not one of them is married, but it is

Jane, the eldest, whom she seeks to marry off first. The situation of a younger

sister marrying before an older one was considered embarrassing and something

to be avoided; a married woman automatically attained seniority over her older

unmarried sisters.

For many other nineteenth-century sets of sisters, marriage

at any point was not in the picture. The Bronte sisters, Charlotte, Emily and

Anne, were in fact three of five daughters (the eldest two Maria and Elizabeth

having died as children). Such were the close bonds between the sisters that

none married during the lifetime of the others. When Charlotte finally tied the

knot in 1854, it was after the death of her two sisters. She herself passed

away soon afterwards from pneumonia whilst pregnant.

By 1850, there was a popularly perceived ‘surplus of women’

in the population – partly due to the fact that the mortality rate for boys was

higher than that for girls, partly because more men worked abroad in the armed

forced or had emigrated. By 1861

there were 10,380,285 women living in England and Wales but only 9,825,246 men.

This meant that marriage for some women was unlikely. Unmarried middle-class

sisters often lived together to minimise expenses and were often supported by

small annuities bequeathed from their parents’ estates or by working brothers.

In other cases, sisters who married well could become the

centre of important cultural networks. Sisters Alice, Georgiana, Agnes and

Louisa Macdonald, (four of the seven) daughters of a lower middle-class

Methodist Minister leapt from obscurity when they got hitched. Georgiana and

Agnes married the famous painters Edward Burne-Jones and Edward Poynter

(President of Royal Academy) respectively, whilst Alice became the mother of

the future Poet Laureate, Rudyard Kipling and Louisa, the mother of future

Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin.

In these close-knit family circles of Victorian and

Edwardian Britain, it seems reasonable to suppose that had one of your female

ancestors died, her husband might have considered marrying one of her unmarried

sisters – another blossom from the same tree, as it were. But the practice of

marrying a deceased wife’s sister was actually forbidden by law until

1907. This is because those who were

already connected by marriage were considered to be related to each other (by

so-called ‘affinity’) in a way that made it improper for them to marry. Between

the Marriage Act of 1835 and The Deceased Wife’s Sister’s Marriage Act of 1907,

a man wishing to marry his deceased wife’s sister was treated as if he were

considering incest! During that period, the only men able to marry their

deceased wives sisters were wealthy ones who could afford to do so abroad such

as the painters William Holman Hunt and John Collier.

|

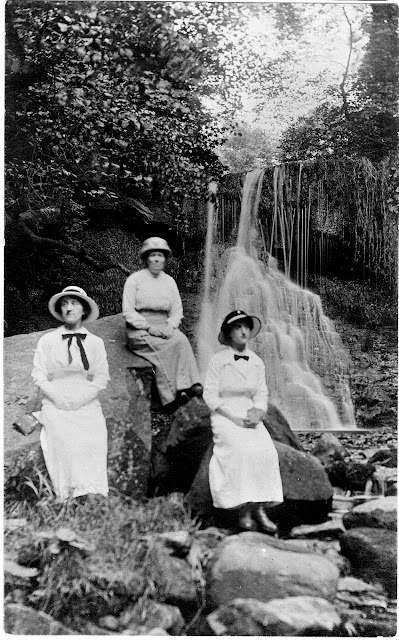

| Symes sisters, Phyllis, Emmie, and Jenny, c. 1908, Hull. After the death of their father and two younger

sisters and before their own marriages, my great aunts (sisters Emmie, Phyllis

and Jenny Symes) took on financial responsibility for their mother and younger

brother, Jack. An example of ordinary sisters working together for a common

goal, all the girls worked for Marks and Spencer (then a newly emergent

company) first as shop assistants and then as manageresses. Their work took

them across the North of England from Manchester to Hull, York and Birmingham. |

Sisters and the Camera

Sisters can often be identified in Victorian and Edwardian photographs by their matching outfits. There was a particular craze for dressing daughters alike in the mid Victorian period (c 1855-1885), particularly among the upper and middle classes who aped the daughters of Queen Victoria in this respect. Even sisters who were far apart in age would be portrayed in matching garb and young adults as well as small children also followed this trend. The matching could extend to hats, boots, jewellery and even to the mirror-like poses of the sitters. Sometimes sisters would differentiate themselves from each other by a minor detail of dress such as a corsage worn on one side of the bodice or the other, or extra trimming.

The relative ages of sisters in photographs can be deduced by the length of the dresses they wore – with the hemlines of older girls being longer. Another clue to the age of a girl is the styling of her hair, with younger sisters wearing their locks down (loose or in ringlets) whilst their elder sisters wore it up. Whilst the fashion for matching dress predominated amongst the rich, working-class sisters were also sometimes portrayed in identical ‘Sunday Best’ outfits.

When interviewing family members about their memories of groups of sisters in the past, be careful. Girls are characteristically remembered by reference to their looks, (for example, ‘the beauty’, or ‘the Plain Jane’); or their marital status and propensity for producing children, (‘the spinster’, ‘the mother of ten’). Other descriptions may be equally distorting; Queen Victoria’s five daughters have recently been described as ‘vivacious, intelligent Vicky; sensitive, altruistic Alice; dutiful, dull Lenchen; artistic, rebellious Louise; and shy baby sister Beatrice.’ This over-simplistic labelling and differentiating of sisters won’t necessarily help you to understand what your female ancestors were really like.

|

In the twentieth century, the public continued to be

enthralled by many other sets of sisters. The Pankhurst sorority, Sylvia,

Christabel and Adela, derived energy from their sisterly bonds in their

struggle to secure the vote for women, whilst sisters Vanessa Bell and Virginia

Woolf (said to have been sexually abused by their two older half-brothers)

produced unusual and startling works of art and literature. Meanwhile, the complex

political situation of the mid-twentieth century is often described through the

antics of one of the oddest of all groups of upper-class sisters – the six

Mitford girls – who ranged in sympathy from Fascist Diana to Communist Jessica.

How exactly our own great-grandmothers interacted with their

sisters depends, of course, on many factors - on the size of their families,

for instance, on the age spacing and birth order of the children, on the class,

ethnic and cultural traditions of their family as well as on their individual

personalities. But whether characterised by harmony or tension, there is no

doubt that sisterhood was an important relationship between the women in our

family trees and one that deserves our special attention.

This article first appeared in Family Tree Magazine UK 2010

https://www.family-tree.co.uk/

Click here for more on books by Ruth A. Symes (UK)

Useful Websites

Useful Books

Flanders, Judith. A Circle of

Sisters: Alice Kipling, Georgiana Burne-Jones, Agnes Poynter and Louisa

Baldwin. Penguin 2002

Fletcher, Sheila, Victorian

Girls: Lord Lyttelton’s Daughters,

Phoenix, 2004

Mintz, Steven. 1983.

A Prison of Expectations: The Family

in Victorian Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Pols, Robert.

Dating Nineteenth-Century Photographs,

Federation of Family History Societies, 2005

Symes, Ruth,

Family First: Tracing Relationships in the Past, Pen and Sword, 2013

Click here to see more details about this book

Beautifully illustrated family history books with a difference by a frequent contributor to the UK family history press. I write for Family Tree Magazine UK ( https://www.family-tree.co.uk/); Discover Your Ancestors Online Periodical and Bookazine (http://www.discoveryourancestors.co.uk/); Who Do You Think You Are? Magazine (http://www.whodoyouthinkyouaremagazine.com/). The publishers of my family history books are Pen and Sword Books (http://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/) and The History Press (http://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/).

For women's history and social history books - competitive prices and a great service - visit:

#ancestors #ancestry #genealogy #familyhistory #familytree #ruthasymes #searchmyancestry #sisters #familyrelationships #Victorian